Begin with the end in mind, act on your present

'Beginning with the end in mind' is not the aspect of outcome-thinking people struggle with. Here's where many go wrong and what to do instead.

What is meant by ‘Begin with the end in mind’?

This phrase was popularised as Habit #2 in Stephen Covey’s ‘The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People’. The intent as explained in the book was for a feedback mechanism to check that actions in the present were really steps aligned with where you were trying to arrive in the future.

One of the suggestions Covey makes was drafting a mission statement. This is a sensible action and provides a reference point to check your plans. A challenge is there may be many steps between your present and realising your mission. Validating present actions against a distant goal is still very challenging. More on this later.

In Amazon, the idea of ‘Working backwards’ is used to describe starting with the needs of the customer and then working out what might need to be achieved to fulfil those needs. This was a topic, among many others, covered by ‘Working backwards’ by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr, both former Amazon executives.

How is ‘Begin with the end in mind’ sometimes interpreted?

There’s a more fundamental issue with how thinking about the future often translates into organisations. A common pattern you can observe in most organisations, in some form or another, is the act of looking at a desired future and then identifying it as a list of gaps in the present.

An indicator this may be happening is when there is a long list of activities an organisation is planning to commit to with a presumed long-term future benefit to be realised some time down the line.

For instance, you will often see this behaviour when maturity assessments are carried out. A fixed set of criteria will presume a fixed, universal view of the future is the preferred one for any organisation. The output of the maturity assessment is a long list of actions which if completed will presume the organisation has reached a new matured state. That is, the collected sum of the activities results in the organisation being improved to its desired future state.

Another example may be the mitigations from audits. Audits may be a slightly more acceptable example as there may be some evidence that similar organisations may present lower chances of realising risks should certain controls be in place. Such causality and evidence are not always collected and audits regularly resemble maturity assessments.

By far the most prevalent form is from leaders presuming that the actions conceived have a causal relationship with the target future state. For leaders taking the positive step of communicating a mission and or vision, it starts to dissemble when what follows is the list of projects, programmes or pillars that follow.

The positive act of considering the long-term goal quickly becomes the reason for a strong commitment to compounding untested assumptions.

While acting without a view to the future may limit the potential success of an organisation by missing out on opportunities to test its actions are successfully moving it in the right direction, this alternative is not much better.

‘Present thinking’ versus ‘Gap thinking’

https://twitter.com/cyetain/status/971753487586521088?s=20

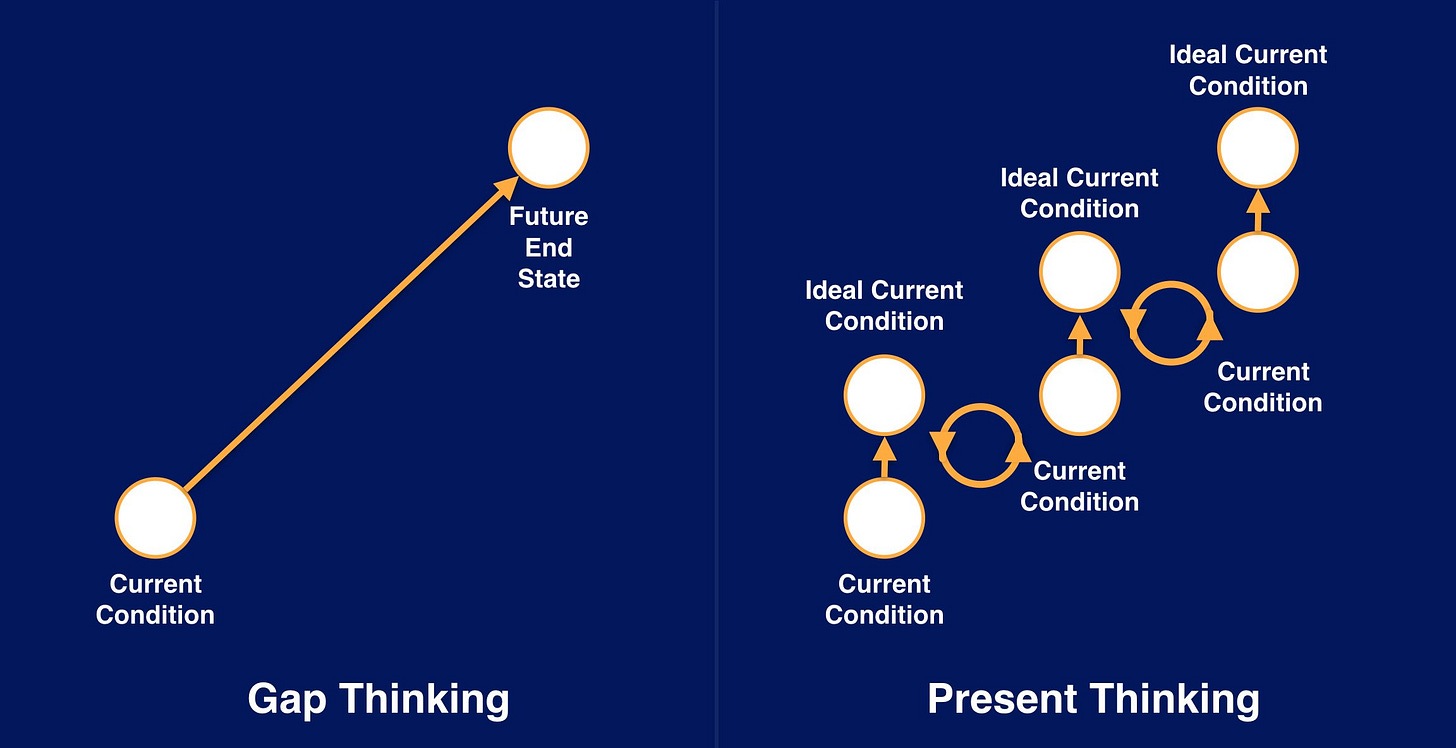

Jabe Bloom articulated this as the difference between ‘Present Thinking’ and ‘Gap Thinking. Bloom, who credits Russell Ackhoff’s ideas of Ideal Present in his book ‘Idealized Design’, visualised and documented the difference in the tweet above and later in collaboration with John Cutler and Amplitude further refined the distinction with this visual:

This was enough for me to recognise the issue and to hint at what must happen to improve upon ‘Gap Thinking’. Jabe promises more on this topic in his dissertation. Whilst we are waiting for that let’s consider what we can do differently to more constructively move from our present towards our desired future.

What to do instead?

Use the future to orient you

Understand causal links

Establish feedback loops

Use the future to orient you

When I think about the future I think of something which is moving. So a simplistic analogy is one of a rocket travelling to the moon. The moon is moving and the rocket is moving. The path of the moon may be predictable but where the motion of firing the rockets will take us less so. So we are checking our instruments after each burn and adjusting our trajectory. Our path to the destination is a series of adjustments from where we are at that point in time to course correct towards our goal. It is not a preordained path we simply follow.

Of course, the future and our place in it is dependent on infinite interactions and what success looks like continues to evolve so, as I said, this analogy is simplistic but highlights a few critical concepts.

Understand causal links

I like to think of the future as something we can orient ourselves towards. Without thinking with the future in mind we can take actions which we assume are positive steps forward but in reality could be taking us in any other direction.

Our planning, like preparing for a rocket launch, involves understanding the relationships between the entities involved. How do we believe they relate to each other? Of course, not everything is as life and death as piloted spaceflight so these tend to be hypotheses in an organisational context and not always mathematics or applied physics.

Hypotheses can be thought of as supposed causality which can be tested. I like to think about where we’d like to be in a longer-term time horizon and then ask ourselves, ‘what would need to be true’ for our longer-term goal to be realised? This will often identify desirable nearer-term goals which are more specific and more achievable in the nearer term.

You can continue to ask this question of each new subgoal as you work backwards towards the present using ever shorter time horizons. As you reach the present time horizon you can include your understanding of your current state. You now have a chain of hypothesised connections between your long-term goal and your present state.

What is evident is that many dependent assumptions are between you and your goal. It is also apparent you can likely only test the nearest assumption to your present to see if you can change your present condition positively in the direction of the future.

Establish feedback loops

And so like the instruments on the rocket and at the home base, it’s the sensors and other information about where we are, how fast we are moving and where our destination is that is critical to reaching our goal. The act of taking action and immediately seeing what the effect was and updating our understanding of where we now are.

Does this resonate with your working experiences? This publication explores the many aspects of this style of outcomes planning and what is required to establish useful feedback loops to act on. Share your experiences or challenges in the comments.