Decisions within organisations are influenced by hard and soft incentives

Fomenting significant change in an organisation is hard. Any attempts that don't consider the different types of incentives at play in an organisation will fail.

Improving an organisation such that the change is both significant and resilient is very difficult. In the worst examples of failed change within organisations, the attempts at change are lists of big-scale activities based on what leaders reckon may work. The benefits, if any, are short-lived and the unwanted side effects long-lasting. Even thoughtful attempts, to apply ideas that worked elsewhere, can have about the same lack of success.

Organisations can be thought of as ecologies of interdependent systems. Most of these systems are patterns emerging from people’s behaviour interacting with systems and the behaviour of others. Improvement can be thought of as interventions in these systems. By thinking about change in this way we can be thinking about what we can try out to bring about the effect we are looking to achieve.

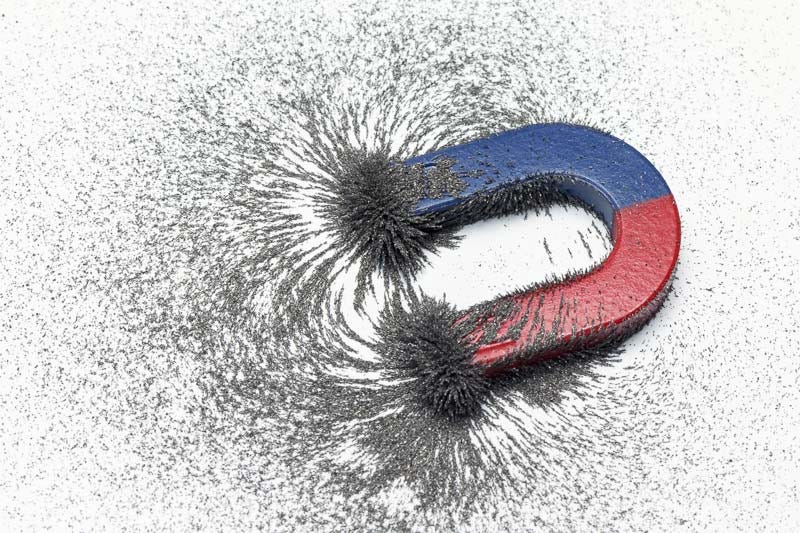

I like to think of the many incentives and disincentives operating within an organisation as magnets which attract or repel different behaviours. For example, if leaders regularly publicly praise only one type of activity then they can expect that activity to be the dominant activity.

An example from closer to home

I will use an example to illustrate the idea but please note this example is oversimplified as it deals with toddlers which are vastly simpler than adults in a work setting. As a father, I am finding an example of how incentives influence behaviour in raising our son.

The best advice I read which has helped my perspective on positive reinforcement and its limits approximated to ‘don’t repeat anything you don’t want to repeat again in the future’.

For my wife and I, we realised we had to make a stand with the use of the dummy and other crutch behaviours we were using to settle our son that had outlived their usefulness. If we didn’t want a dummy to be a permanent fixture we’d have to make a change. If we didn’t want him to cry every time he wanted something we had to stop giving him things every time he cried.

I write about this in more depth in this post:

And now, back to work

Bringing a variation of this idea back to change in an organisation; some companies that skew towards being feature factories also have a culture of “attaboys” over email every time a feature is released. I am not saying it is the cause of the ‘feature factoriness’ - but it may be an inhibitor to changing from being one.

Why? After all, it’s only low-effort celebration and praise, what harm could it do? If we think in terms of incentives, and we have the goal of shifting the organisation towards more successfully addressing customer needs then this behaviour could be an incentive which is reinforcing the wrong behaviours. It may influence teams prioritising shipping features which may be crowding out other desirable but less visible behaviours such as addressing quality or operational issues that also affect customers.

The classic is the shipping of many features correlating with a gradual decline in quality and reduction in ease of delivery. The problem can be both with leadership and product teams — product teams can create this situation by being narrow in what they communicate; well-intentioned leaders will provide positive encouragement in response to positive news. Good leaders will expect and ask for more. Good product teams will provide regular updates on failure, learning and more.

I continue this post in part 2, here:

Share with me in the comments some of the incentive structures (whether from those above or ones I have missed) that you have noticed in your organisations. This input will inform later posts where we will explore what we can do to encourage desirable effects and what we can do to limit undesirable effects.