Never waste a good crisis — part 3 — Failures & how we addressed them can teach us evergreen…

What enduring lessons can be taken from how we respond to failure?

What a crisis teaches us about planning & prioritisation

What can this teach us when thinking about Product development? I will walk through the concepts and takeaways that this live example of COVID-19, which touches every business and every consumer, can teach us.

Start part 1 here of my 6-part series here:

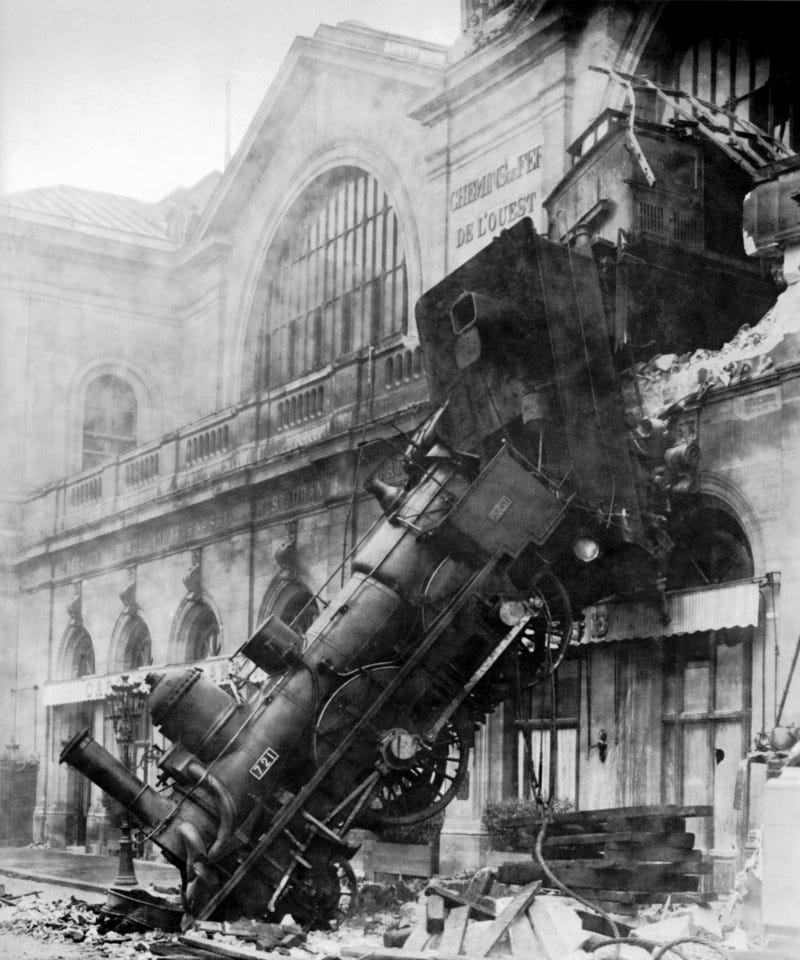

Failures and how we addressed them can teach us evergreen lessons

The opportunities of eliminating paper, working across geographies, working from home and many other benefits of technology evolution have been spruiked from the ‘Innovators’ (referencing the adoption curve) and by the armies of consultants that follow in their wake. Yet many organisations have yet to fully capitalise on these opportunities years after the value of these changes has been demonstrated in the market. Why?

As I shared earlier, most businesses already saw the value because they had undertaken or planned and budgeted for expensive digital transformation programmes. One barrier, however, is the sheer scope and length of such programmes. Even once embarked it may be years before a lot of the capabilities were deployed for the benefit of most of the people in an organisation.

My hypothesis is that plans framed in terms of actions or solutions are at risk of bloat because there isn’t a context that simply connects them to specific problems or needs or at very least orients them towards the organisation’s purpose or the value it provides.

Sometimes Project Management approaches require problem statements to be defined — this is great in principle. The issue is these are overlaid on to delivery plans; our human bias is to gravitate towards the certainty of something concrete such as a plan or an action and away from the uncertain such as whether or not doing something may impact us in the distant future.

This bias assures most of the activities conceived and ‘put in the plan’ are likely to stay part of the plan. They are ensconced in the big bucket of solutions required to complete the project regardless of the efficacy of the activities and the actual problems they are supposed to address.

Challenging work in the plan such as to test if they address the most important need in the optimal timeframe is hard when context for the work is limited, such is often the case for work planned ‘activity first’. This is because these questions are, by their nature, uncertain and, as a result, are a higher probability to be deferred. The effect is a focus on actions superseding actual problem-solving.

Why did the virus help organisations see their value more clearly?

When the virus hit, when people didn’t trust in physical interactions anymore, when authorities acted and instated lockdowns — for an instant we saw very clearly the few things that actually mattered to our customers which would determine if we could operate and trade or not.

We could see all the things that without change could not happen anymore. Until change was instigated, just existing would be expensive. So in this context, ‘Never waste a good failure’ was more about whether we would waste a cluster of failures — the many points of failure between us and delivering value to our customers.

What did each of these gaps tell us about what was important? With this knowledge plans on how to get back to an operating state and be valuable to customers were easier to define, the cost of each day of inaction was clear and a significant motivator to keep things lean and implemented quickly, often iteratively in parts as things were ready.

From this we learn that Understanding the value of an activity:

provides a framework for prioritisation,

helps to understand what progress looks like

and can function as an incentive.

Why are there approaches that appear unthinkable until a crisis comes?

So what did organisations everywhere do differently in response to the crisis that may be an ‘… opportunity to do things that you think you could not before’?

They did not comply with their budget plans — below on revenues in many cases whilst undertaking significant unplanned spending. In fast-changing times it’s worth challenging whether yearly planning cycles make sense when the rate of change in the business environment is far more rapid than before.

They adopted either formally or more likely informally agile practices; frequent short planning, short execution cycles and frequent review and adaption. Cross-functional collaboration and coordination were essential. It’s likely that cross-functional groups oversaw most of the significant changes. Feedback loops with staff and customers were established on more specific questions and engaged with greater frequency.

In an environment that was widely understood to be changing and uncertain, uncertainty was acknowledged and organisations tried things, learned from failures, acknowledged those failures and adapted far more readily than in normal times. Those that didn’t acknowledge issues quickly heard about it (because people’s worries were acute and power distance was overcome by self-preservation) and thus companies soon did learn and adapt behaviours or failed.

What is the lesson here? Many current practices of organisations do not stand up to scrutiny or indeed when tested by reality.

Furthermore, bias can lead to blind spots in this and thus we should assume this is true until proven otherwise.

As Mike Tyson said (and I have this on the good authority of the internet):

Next, I will look at how crises help us challenge our assumptions and how we might leverage the knowledge of why this works for a benefit during normal times:

This post is part of a continuing series of posts: