Edited: Unchallenged assumptions #1 Hierarchical reporting structure

Hierarchical reporting structure is an unchallenged assumption, the top-down tree-like structure used in most companies. What is it, why does it exist and when does a different approach help?

In the introductory post for this series, I introduced the idea of unchallenged assumptions in organisations that had become so accepted as the way work is done that they become very difficult to challenge, even when doing so would be very impactful:

Seven unchallenged assumptions stunting your company's growth

Early in your career, you see how others do things, and you adopt through emulation. Like baby ducks, we imprint from those we see around us. It’s one of the ways we learn. This instinctual approach ensures we learn the ropes quickly but may lead to some practices being adopted without much challenge.

The unchallenged assumptions I had identified were:

Hierarchical reporting structure.

There are others, and I encourage you to share your examples in the comments, but these were the most prevalent ones I’ve experienced.

Hierarchical reporting structure

The starting point for most organisations in how they organise is who reports to whom. For most, this is a reporting hierarchy with leaders at the top of the tree and their reports below them. If there are multiple levels of management, this pattern repeats with the leaf nodes being the individual contributors.

There are exceptions to the design of organisation charts where leaders are at the top and the tree expands under them, but they are rare. You can tell they are rare because the most common software for rendering organisation charts assumes it works this way.

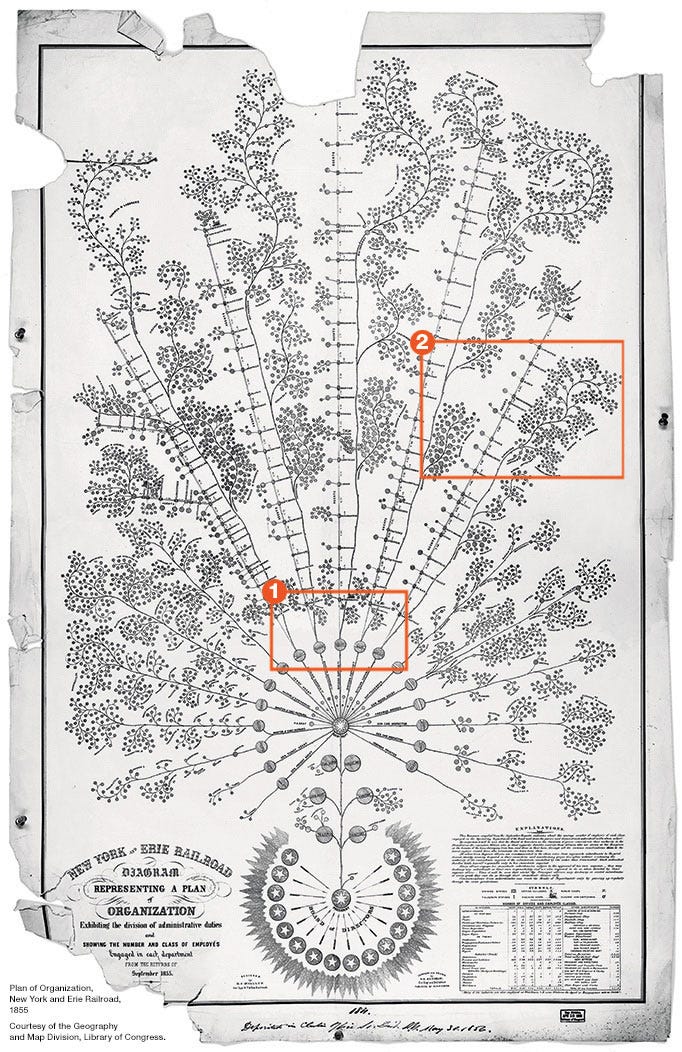

It wasn't always this way. Here’s an example of the New York and Erie Railroad organisation. The top leadership are pictured at the bottom of the reporting structure, not at the top as is customary. I find it remarkable that the diagram also mirrors the train stations themselves in an era when the size of the workforce to staff all the stations and track maintenance was significant. In modern organisations, we’ve lost much of the connection for how people relate to the value provided. In a future post, I will cover this issue in more detail when I examine the unchallenged assumption of ‘Functional separation’.

The assumption

The core assumption that drives the hierarchical structure as the dominant paradigm is that the needs of managing someone in terms of performance, personal development, and task focus (sometimes described from the perspective of management as ‘content authority') are the same and that a single individual is needed to manage these.

Matrix organisations often split the personal development from the task focus, with the performance being an assessment from at least two managers from each matrix dimension. In most cases, I wouldn’t recommend a matrix organisation as a better approach as it is two strong hierarchies, which provides similar disadvantages of the hierarchy but with twice the confusion. It does, however, provide an example of challenging the responsibilities that are assumed to be associated with line management, and these are firmly entwined with the unchallenged assumptions of hierarchical reporting structure. Part of challenging a hierarchical reporting structure involves challenging the responsibilities associated with line management.

The desire for consistency across an organisation can provide significant friction in moving beyond this structure. For Human Resources departments, making such a change can be seen as introducing considerable inefficiencies in managing the processes they are responsible for.

Tied in with this are the assumptions around the direction needing to be strongly aligned with the business owner. For instance, having an individual responsible for something can be a powerful approach to ensuring alignment and focus. But this is not the only way to achieve firm and aligned focus - teams with a strong understanding of the challenges and customer needs with a specific and measurable understanding of what represents meaningful progress can have the same or better alignment and focus than under a single manager’s responsibility.

The team can own an area of responsibility or a goal. They may still be accountable to others but may not be strongly tied to their reporting line relationship. Unfortunately, many organisations haven’t developed this ‘muscle’ to clarify goals and responsibilities. As such, the model of an individual reporting manager who manages each direct report's performance against achievement of objectives is often the ‘go-to’.

When a different approach may benefit

There have been many efforts to work in alternative structures beyond the classic reporting line structure. Approaches such as holacracy and others are well documented. There are many exciting ideas and approaches among these. Still, for this post, I wanted to share simpler adjustments that can shift the incentives that operate on managers and teams to demonstrate the potential value of challenging this assumption. The examples are from successful changes made on a reasonable scale (a SaaS company’s product development capability of 200+ people).

One path we took was to change the responsibilities we expected of software development managers. We achieved this by making the responsibilities of what to work on and assessing progress the team’s responsibility, not the manager’s. This didn't remove the need for line management. Still, it splits some responsibilities, often coupled with line management responsibilities - another side effect of organisational norms being considered default and unchallenged.

Similar to matrix management, this approach splits management responsibilities apart. Unlike a matrix management approach, which might assign responsibility for the ‘content authority’ for task focus to a management structure aligned to ‘business owners’ and the remainder of responsibilities to a functional management structure such as ‘software development’, this approach took the responsibility for managing software delivery away from the line manager altogether.

The benefit was less arbitrary interference from managers with less skin in the game but more personal reputation and feeling of obligation to be concerned with. It’s human nature to feel that falling short on delivery commitments might negatively impact the manager. It becomes an issue when it undermines the decision-making at the team level, which is made up of adults who are experienced professionals. More essential for us than arbitrary delivery milestones were the outcomes, both the effects over the short term and the enduring effects over the long term. For this reason, we chose to break the incentive, which led to behaviours that contributed to the perception that delivery mattered over outcomes and also reduced the team’s ownership of the outcomes.

We needed motivated teams with the right capabilities to achieve by doing the right things each day and for the long term. That means empowered decision-making rights were the most relevant information, the context to make informed decisions and the capability to decide on the right distribution of effort to do what was best for the customer and the company.

The team was still accountable for what they delivered but how the accountability functioned differed. They shared their results to the organisation frequently. They responded to questions from people across the organisation - leaders, sales teams, customer service teams, other software teams, operations etc.

What was left then for reporting managers to do? This change can free up reporting managers to focus purely on the following:

Be the person in the corner for that employee, supporting their training and development, career growth, and navigating issues affecting them personally and how they engage with the organisation. Doing this well for several team members takes substantial time and investment. Being consistently available for 1-on-1’s, proactively pursuing development opportunities, providing great feedback, helping connect them to information and people - all of these things can get routinely deprioritised by managers in favour of attention to delivery matters. Its not impossible to balance both as an experienced manager but when the situation has been entrenched for some time where delivery took priority, separating this connection can have a substantial benefit.

Individual performance management would remove or radically adjust the approach to individual performance management upon observing it is working against what the company is striving for. Unfortunately, it is rarely a short- or medium-term option, so where individual performance management exists, it will continue to be a critical responsibility for a manager. In a future post, I will cover the unchallenged assumption of ‘individual performance management’.

Provide relevant context to the individuals and teams under their care so that they can make the best decisions possible.

The benefit for the team of this approach is that there are now managers with more bandwidth to support their development and other needs. These are often essential areas under-attended due to the manager feeling personally responsible for the team’s achievement of objectives.

This concept may be jarring to think about at first glance as it face value will seem wrong, ‘what manager’s not on the hook for a team’s objectives?’, but in practice, teams of professionals who are clear on their goals will do the work to the best of their professional capability. Not unlike this scene from the film Contact, we add ‘minimal protection’ because we don’t trust that it would be safe to do otherwise:

The manager instead assesses the team's capabilities to fulfil the team's responsibilities. They can support each individual’s ability to contribute to the team’s capabilities and they can address individual’s development needs. Our goal was to fulfil the promise that by working with us, you would learn more than working anywhere else.

In the upcoming posts, I will provide my experiences in identifying and challenging the next six examples of ingrained assumptions shaping work and limiting value in organisations listed at the top of this post.

Have you noticed this unchallenged assumption your organisation? Is this something that has been challenged or done differently in your organisation? Do you have additional examples? If so, please share in the comments.

This post covers some similar ground as mine and shares some of the patterns emerging in the software space relating to how some companies are challenging the longheld assumptions relating to line management and the responsibilities of leadership

https://lethain.com/layers-of-context/