'Are OKRs Management Malpractice?' Part 2: It’s hard to know which flavour of OKRs we are discussing

When OKRs are criticised (which is fair enough; there's plenty to criticise), it can be hard to know which version is being referred to. OKRs are a moveable feast. Here's why.

In my earlier post, I explored whether ‘OKRs are Management Malpractice’, as Noah Cantor posits, or whether some disconnects make it difficult to draw a conclusion:

My theories about the disconnect are as follows:

It’s hard to know which flavour of OKRs we are talking about.

It strongly depends on what you hire OKRs for—management vs alignment.

There are terminology differences between disciplines, such as inconsistent definitions of goals, objectives, and outcomes.

What can’t be argued in terms of scenarios where OKRs can go astray:

Some (most?) bodies of OKR documentation describe pernicious and flawed approaches to OKRs.

Many (most?) companies ‘hire’ OKRs for purposes other than those recommended by experienced OKR practitioners—alignment.

Many (most?) companies that deploy OKRs do so in ways that make them a chore/bureaucracy/expensive overhead, a management control method, or worse.

The responses to Noah’s question on LinkedIn demonstrated that the average software development professional is unaware of various approaches to implementing OKRs. That’s fair enough; OKRs are not a formal method. Everyone is free to describe the approach in their own way. I’ve covered this in various posts, such as this one:

More importantly, it makes OKRs difficult for people to explore for the first time and requires developing expertise in the field or finding someone to guide the organisation. For an organisation to become competent, it ultimately requires developing people proficient in using evidence for decision-making, OKRs, and other adjacent disciplines.

It makes a complicated topic moreso as it extends the surface area for critique. For instance, as a participant in the community who has used OKRs extensively, I am very familiar with where OKRs have evolved in 2024. Noah, newer to the topic, is discovering the full body of thinking, past and present, all at once. For instance, his post refers to a 2016 Christina Wodtke post suggesting OKRs should cascade. Having followed the work of influential voices in the OKR practitioners community, I know Christina shifted her perspective on this topic in 2020. More on this later.

Or in trying to understand what specific assumptions OKRs kept from MBOs when almost every aspect of MBOs changed as they evolved into OKRs—e.g., from individuals to teams, from private to public, from linked to reward; from activities to outcomes; from cascaded to aligned. If every part of a car is replaced, is it the same car? OKRs have changed in the decade since Measure What Matters was published.

The dissonance may be similar to a critic choosing to review popular software. It's at v4.5 after a decade of refinement, but then they install v0.1c and write a scathing review about its flaws.

OKRs have evolved substantially over the last decade since they entered the global zeitgeist. Practitioners write about their experiences and attitudes towards some of the practices associated with OKRs shift over time.

If applied today, I agree that many of the elements of previous iterations of OKRs (and their forbears, MBOs) are indeed Management Malpractice. OKRs have evolved a lot over the years, so let's take a short walk to see the evolution to help discern where various concepts came and left.

A Brief History of OKRs

The history of OKRs starts with MBOs, which evolved to OKRs at Intel, again as they were popularised at Google and then other Silicon Valley companies. They continue to evolve as they have been adopted globally.

Drucker and MBOs

It’s no secret that OKRs owe some of their history to MBOs attributed to Peter Drucker. However, Drucker was likely distilling practices that go back further still, no.

Management by Objectives (MBOs) is featured in Peter Drucker’s book The Practice of Management (1954) and later further developed in his student George Odiorne’s book Management Decisions by Objectives (1969). They build upon ideas presented in Mary Parker Follett's ominously titled 1926 essay, The Giving of Orders, which introduced the rather progressive idea of distinguishing between power-over and power-with and that together, managers and employees could discover the appropriate responses to a situation.

Management by Objectives has the following properties:

Top-down goal-setting - start by identifying the organisational objectives.

Managers set goals for individuals derived from the organisation’s objectives. These goals describe the change desired—‘the what. ‘ They were generally not visible, being 1:1 contracts between the Manager and Direct Report.

Objectives were measurable, and progress was monitored. MBOs encourage using Targets, which introduces all the challenges of perverse incentives.

MBOs are linked directly to remuneration and financial incentives.

Is a management approach and is designed around the ethos of ‘what is measured is managed’.

Andy Grove and iMBOs (later renamed to OKRs)

Andy Grove sought to improve upon MBOs at Intel, first reformulating them as ‘IMBOs’ (“Intel MBOs”) and then as Objectives and Key Results (“OKRs”). Over this short retelling of OKR history, you will notice a steady evolution of this branch of goal-setting. The biggest changes from MBOs to OKRs were:

Make them public — Andy Grove wanted to see change by moving away from MBOs, and a big part of this was improving transparency and increasing the opportunities for everyone in the organisation to participate in alignment rather than this being the domain of management.

OKRs are team-based for aligning a group more than between a manager and an individual.

Focused on change rather than measuring performance

Not tied to individual performance incentives or directly to organisational incentives.

The ambiguity of use as a management or alignment approach is introduced.

John Doerr brings OKRs to Google and Silicon Valley (and a diversion in cascading vs. aligning OKRs)

John Doerr, author of Measure What Matters, a book that helps popularise awareness of OKRs, was a student under Andy Grove at Intel and, after working with OKRs there, brought the concept to Google as a member of their board. The idea took off there, and later, as Google's use of OKRs became more public, OKR's popularity increased with adoption across many Silicon Valley companies and then adoption globally. OKRs continued to evolve with adjustments such as:

Emphasis on objectives to be ambitious - the stated purpose of this is less about gamification or moonshots (although no doubt managers at Google experimented with both a mix of happy accidents and detriments) and more about encouraging lateral thinking. This is the primary benefit of stretch - there’s no consequence to falling short - but by starting with a goal which, to begin with, is not completely known how it may be achieved, there is an exploration of adjacent and lateral opportunities. How able and supported teams are to explore options should inform whether to apply this approach.

Emphasis on focus—the guidance is for fewer objectives (2-4) and key results (2-4). As a constraint that encourages explicit agreement on what will and will not be the focus.

Failure is acceptable and an opportunity to learn. OKRs are particularly popular among software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies in highly competitive contexts. Teams in these companies hypothesise, generate options, choose a change to experiment with, make the change, observe the impact, and adjust.

Achieving less than 100% is not a failure—usually, 60-70% would be considered a success.

Focused on a mix of focus, motivation, and alignment.

Most examples were not defined as outcomes but as activities.

Most key results were also outputs or activities, rather than measuring leading indicators that may provide evidence of progress.

As I have written, the structure of John Doerr’s book Measure What Matters was brilliant in introducing the concepts and variations of how OKRs were being applied in various companies. In other ways, it set OKRs on a course that has caused countless company issues and contributed to confusing the application of them usefully. This post covers my complicated relationship with this book:

In my post, I reflect that the book's form of surveying practices across companies was good for introducing how OKRs may be relevant for your organisation. Still, it does not suggest that every example reflects how the author would recommend it be implemented. Of course, not to be completely exonerated, John also provides plenty of poor examples based on today’s standards.

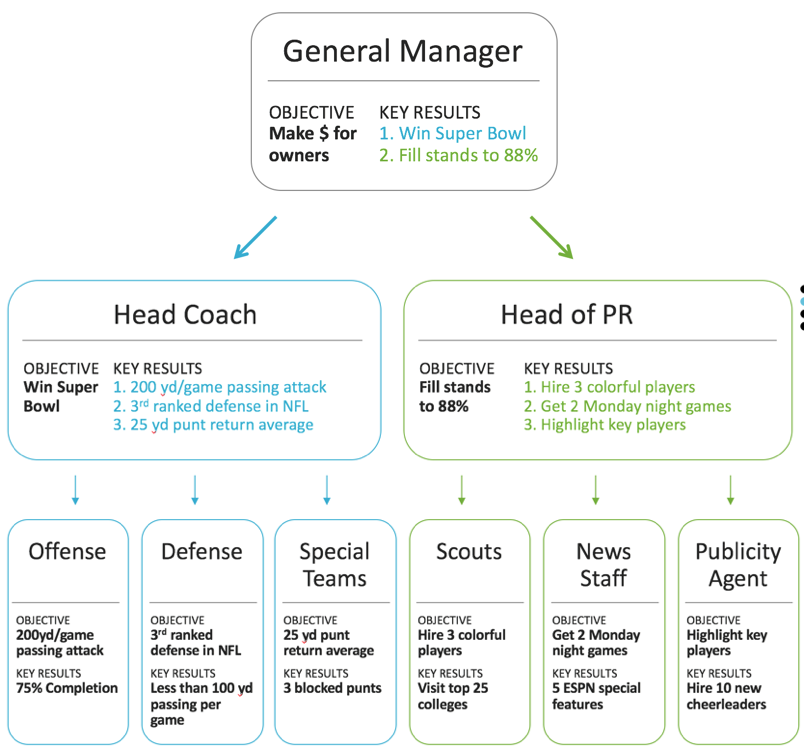

Unfortunately, Measure What Matters also popularised various practices that don’t have heartfelt supporters today. The football team example captured the imagination of people intrigued by OKRs. You might have seen it do the rounds in various forms over the years. It's an example illustrating a cascading model using a purely synthesised example. No football team has worked this way.

From this excerpt, John raises some issues and risks with cascading in the book (2 of 4 are listed here). However, many reformulations of this example, such as this version below, mememetically caught fire across blogs and social media sans the calls for caution. Many shallow book readers will swear that this is how OKRs should be implemented despite the author providing 4 reasons why it will likely not work.

The simple promise of alignment must outweigh the mind’s usual defences because all it takes is one enthusiastic leader to see this example, even in otherwise deep-thinking organisations. One can find themselves on a futile quest for a few quarters to discover what can be gleaned from a little more consideration. So stubborn and sticky, this concept persists today despite consistent warnings of its folly, such as this post by Felipe Castro.

Noah quoted a Christina Wodtke post from 2016, referring to OKRs cascading. Christina Wodtke addressed and evolved her thinking on cascading, captured in a post she wrote in 2020. Christina still calls it ‘cascading’, but from the post, it’s clear that how this is approach is consistent with what Felipe described as ‘aligning’, and that is the terminology I prefer, given the implications of one approach to the other.

Itamar Gilad, former Google Product Manager on Gmail and Youtube, and author of OKRs Done Right and ‘Evidence-Guided: Creating High Impact Products in the Face of Uncertainty’ has shared that within Google (now Alphabet) over the years, the approach to using OKRs shifted from the fairly output and activity style examples that dominate Measure What Matters to more outcome-oriented objectives with evidence supporting an aligned understanding of what successful progress would be. It’s a massive organisation with many sub-companies, so I am sure there’s plenty of variance there, too.

All of these methods have some common risks.

Employees become overly focused on quantitative measures.

Forgoing other priorities that are important for the correct functioning of the organisation.

Using the team's goals as reasons to not cooperate with other teams, even when doing so, may serve the organisation.

Investing in improving the organisational capabilities for decision-making and using evidence for decisions goes a long way toward addressing these issues in most instances. The benefits are a reduction in the highest-paid persons’ opinions prevailing (HiPPO) and other biases having outsized effects.

OKRs in 2024

Let’s move forward to the recent decade, and OKRs continue to evolve. People’s writing, sharing, experimentation and thinking of people (books, posts, videos and other formats), such as those I’ve collected on this list of people who I call ‘outcome thinkers’, many of whom have shaped and evolved OKRs in recent years. Many practitioners, coaches, or others who are in influential positions to guide organisations in OKR adoption, see what is working, and try to improve the approach.

This has seen the following shifts in thinking on OKRs and with a surprising degree of convergence. Hey, a surprising degree of convergence aside, I still write posts poking at continuing areas of divergence, such as my recent post:

The areas where OKRs have evolved in the last decade:

Align, don’t cascade goals—think ‘eventual consistency’ over time rather than force fit within a single period. When leadership provides sufficient context to their teams, the teams are in the best position to assess when to align and when they may have other commitments that put organisational or critical service health at risk.

Objectives are strictly outcomes—I’ve written extensively about this in this publication. Check out the ‘Goal-setting & OKRs’ section for more posts addressing objectives as outcomes. Note: most examples from MBOs and early examples of OKRs were not outcomes. They were mostly examples of outputs or activities.

Key Results are leading indicators of success - think evidence of progress. Another topic I’ve covered extensively in this publication.

Use in concert with KPIs / SLOs - OKRs are focused on change, but against what baseline and improving towards what? How do we know we are sustaining any positive change that was achieved? You can build a common understanding around both what you are changing and what you are sustaining.

Multi-directional alignment rather than top-down setting - the reality that a lot of information in organisations is far clearer when the work or the interactions with customers are happening than where senior leadership are positioned. Aggregation and movement of information have a natural dampening effect. There’s a lot to be gained by effort across the organisation to be clear about what teams are striving to achieve and to sense-check this is understood, not only between management and team but between every team.

Teams write their own goals but evolve in response to other teams’ goals. Write Shared Goals between teams if it helps with alignment, agreement, and cooperation. Form a virtual team if needed. Have a committee adopt an OKR if that’s where the leverage is.

Scrap/update goals when you learn they are wrong - there were quite a few references to being locked into OKRs. Most influential OKR bodies of knowledge by experienced practitioners will encourage abandoning OKRs when learning informs they are irrelevant or impractical to achieve. Sure, there’s the potential for sunk-cost fallacies, but that’s true regardless of the approach to work. How often that happens is more a function of culture.

Use a persistent model to see where the current goal applies leverage in a causal tree of relationships (see Results Maps, Bet trees, Goal Trees, Current Reality Trees/Future Reality Trees, Opportunity Solution Trees, and many more variations. One could even argue some of the same information is contained within Hoshin Kanri) and update the persistent model with what you learn. Use the persistent model for faster goal-setting.

Coherent higher-level goals - organisational and team goals, departmental or other organising factors in larger organisations.

In the next post, I will address the next potential reason for the disconnect:

Do you believe OKRs have evolved substantially from their roots in MBOs, or are they the same concept in a different wrapper? Share your perspective in the comments.

I assume it's being a negligent manager or leader based on your definition. So by extension we are examining is ANY use of OKRs are a form of negligence by managers.

There's no debate that some use of OKRs is reflective of negligent behavior - such as using OKRs for managing teams rather than supporting alignment and awareness across teams, linking OKRs to performance and other incentives, disempowering by managers setting the OKRs for their teams, disempowering by defining goals as outputs or actions on behalf of teams, disconnecting from learning by tracking progress through activities without considering what causal relationships may exist, working without a hypothesis...

But what Noah has put out there and you have asked me to consider (and I have, long before anyone asked me to) is are all applications of OKRs negligence. Albeit Noah qualified his view in his post identifying that link to incentives, cascades, managers setting the OKRs to name a few are the specific concerns he has with OKRs. But you wouldn't find any experienced practitioner recommend any of these practices. So those stripped away, where exactly is your discomfort.

He also suggested he'd instead use goal trees which are all recommended amongst the same set of experienced practitioners (the list of the people I am thinking of when I use this term was linked to from my post).

You mentioned no discomfort with team goals so what of the remaining aspects of OKRs provide the discomfort you have? Is it that they are public? Is it that cultures that use them may expect them used universally? These are all areas worthy of debate. I suspect there will be shifts in these areas true.

Another area worthy of debate is OKRs as targets. A lot of practical applications of OKRs in organisations soften their effect as targets because failure is more than acceptable its seen as learning and that is valued more than the result over a short period. OKRs are most widely used in SaaS businesses currently where competition is fierce and these companies are trying to prevail over the long term, not just juice metrics. But is it enough to not have the destructive effects of targets. It's part of my affection with PuMP - Stacey Barr has designed a performance measurement approach entirely around not setting targets.

Finally there's some discomfort with expressing outcomes separate with the method as per John Willis reference to Deming 'by what method'. But this seems to be based on what you imagine happens. In my experience where teams are defining their goals they also have a rich view on what their hypotheses are and how they will test them. OKRs being for alignment only don't typically define how they approach the activities so they use any of the wide range of options for engaging and theorising and testing their theories. You don't have to take my word for it, plenty of my colleagues have written about their experiences working this way.

Hi Daniel, thanks for this great rundown on the history of OKRs and their various forms over the years.

I’d like you to consider, for 1 minute, that all the forms you outlined above are some form of management malpractice. My argument is that they all stem from one concept- the idea that achieving an objective or gaining an outcome is the purpose of business.

Your newsletter title “Focus on Outcomes” reflects this philosophy.

At first sight outcomes appears to be praiseworthy. As businesses mature and go through “boom and bust” cycles, outcomes feel less sturdy.

A focus on creating joy at work might first appear flippant. At best this is a subsidiary goal. As with all reinforcing loops, flywheels in modern terms, their efficacy comes when tested.

The same with alignment. Who could argue that alignment is not a good thing, until we are all aligned like lemmings on falling off the same cliff.

The test of good management is not how they perform in good times but how they handle the bad times. Ask any receivership business?